You’ll find the following quote near the end of chapter 82…

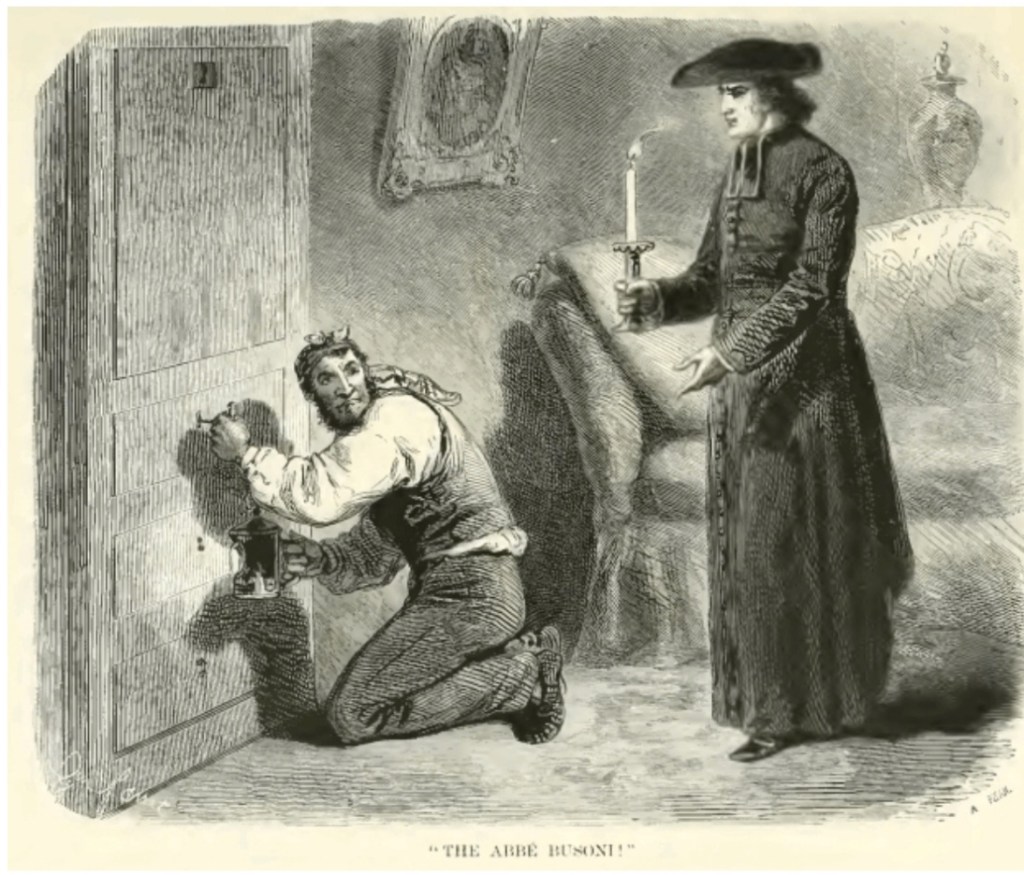

“The Abbé Busoni!” exclaimed Caderousse; and, not knowing how this

strange apparition could have entered when he had bolted the doors, he

let fall his bunch of keys, and remained motionless and stupefied. The

count placed himself between Caderousse and the window, thus cutting

off from the thief his only chance of retreat.

“The Abbé Busoni!” repeated Caderousse, fixing his haggard gaze on the

count.

“Yes, undoubtedly, the Abbé Busoni himself,” replied Monte Cristo. “And

I am very glad you recognize me, dear M. Caderousse; it proves you have

a good memory, for it must be about ten years since we last met.”

This calmness of Busoni, combined with his irony and boldness,

staggered Caderousse.

“The abbé, the abbé!” murmured he, clenching his fists, and his teeth

chattering.

“So you would rob the Count of Monte Cristo?” continued the false abbé.

“Reverend sir,” murmured Caderousse, seeking to regain the window,

which the count pitilessly blocked—“reverend sir, I don’t know—believe

me—I take my oath——”

“A pane of glass out,” continued the count, “a dark lantern, a bunch of

false keys, a secretaire half forced—it is tolerably evident——”

Caderousse was choking; he looked around for some corner to hide in,

some way of escape.

“Come, come,” continued the count, “I see you are still the same,—an

assassin.”

“Reverend sir, since you know everything, you know it was not I—it was

La Carconte; that was proved at the trial, since I was only condemned

to the galleys.”

“Is your time, then, expired, since I find you in a fair way to return

there?”

“No, reverend sir; I have been liberated by someone.”

“That someone has done society a great kindness.”

“Ah,” said Caderousse, “I had promised——”

“And you are breaking your promise!” interrupted Monte Cristo.

“Alas, yes!” said Caderousse very uneasily.

“A bad relapse, that will lead you, if I mistake not, to the Place de

Grève. So much the worse, so much the worse—_diavolo!_ as they say in

my country.”

“Reverend sir, I am impelled——”

“Every criminal says the same thing.”

“Poverty——”

“Pshaw!” said Busoni disdainfully; “poverty may make a man beg, steal a

loaf of bread at a baker’s door, but not cause him to open a secretaire

in a house supposed to be inhabited. And when the jeweller Johannes had

just paid you 45,000 francs for the diamond I had given you, and you

killed him to get the diamond and the money both, was that also

poverty?”

“Pardon, reverend sir,” said Caderousse; “you have saved my life once,

save me again!”

“That is but poor encouragement.”

“Are you alone, reverend sir, or have you there soldiers ready to seize

me?”

“I am alone,” said the abbé, “and I will again have pity on you, and

will let you escape, at the risk of the fresh miseries my weakness may

lead to, if you tell me the truth.”

“Ah, reverend sir,” cried Caderousse, clasping his hands, and drawing

nearer to Monte Cristo, “I may indeed say you are my deliverer!”

“You mean to say you have been freed from confinement?”

“Yes, that is true, reverend sir.”

“Who was your liberator?”

“An Englishman.”

“What was his name?”

“Lord Wilmore.”

“I know him; I shall know if you lie.”

“Ah, reverend sir, I tell you the simple truth.”

“Was this Englishman protecting you?”

“No, not me, but a young Corsican, my companion.”

“What was this young Corsican’s name?”

“Benedetto.”

“Is that his Christian name?”

“He had no other; he was a foundling.”

“Then this young man escaped with you?”

“He did.”

“In what way?”

“We were working at Saint-Mandrier, near Toulon. Do you know

Saint-Mandrier?”

“I do.”

“In the hour of rest, between noon and one o’clock——”

“Galley-slaves having a nap after dinner! We may well pity the poor

fellows!” said the abbé.

“Nay,” said Caderousse, “one can’t always work—one is not a dog.”

“So much the better for the dogs,” said Monte Cristo.

“While the rest slept, then, we went away a short distance; we severed

our fetters with a file the Englishman had given us, and swam away.”

“And what is become of this Benedetto?”

“I don’t know.”

“You ought to know.”

“No, in truth; we parted at Hyères.” And, to give more weight to his

protestation, Caderousse advanced another step towards the abbé, who

remained motionless in his place, as calm as ever, and pursuing his

interrogation.

“You lie,” said the Abbé Busoni, with a tone of irresistible authority.

“Reverend sir!”

“You lie! This man is still your friend, and you, perhaps, make use of

him as your accomplice.”

40160m

“Oh, reverend sir!”

“Since you left Toulon what have you lived on? Answer me!”

“On what I could get.”

“You lie,” repeated the abbé a third time, with a still more imperative

tone. Caderousse, terrified, looked at the count. “You have lived on

the money he has given you.”

“True,” said Caderousse; “Benedetto has become the son of a great

lord.”

“How can he be the son of a great lord?”

“A natural son.”

“And what is that great lord’s name?”

“The Count of Monte Cristo, the very same in whose house we are.”

“Benedetto the count’s son?” replied Monte Cristo, astonished in his

turn.

“Well, I should think so, since the count has found him a false

father—since the count gives him four thousand francs a month, and

leaves him 500,000 francs in his will.”

“Ah, yes,” said the factitious abbé, who began to understand; “and what

name does the young man bear meanwhile?”

“Andrea Cavalcanti.”

“Is it, then, that young man whom my friend the Count of Monte Cristo

has received into his house, and who is going to marry Mademoiselle

Danglars?”

“Exactly.”

“And you suffer that, you wretch!—you, who know his life and his

crime?”

“Why should I stand in a comrade’s way?” said Caderousse.

“You are right; it is not you who should apprise M. Danglars, it is I.”

“Do not do so, reverend sir.”

“Why not?”

“Because you would bring us to ruin.”

“And you think that to save such villains as you I will become an

abettor of their plot, an accomplice in their crimes?”

“Reverend sir,” said Caderousse, drawing still nearer.

“I will expose all.”

“To whom?”

“To M. Danglars.”

“By Heaven!” cried Caderousse, drawing from his waistcoat an open

knife, and striking the count in the breast, “you shall disclose

nothing, reverend sir!”

To Caderousse’s great astonishment, the knife, instead of piercing the

count’s breast, flew back blunted. At the same moment the count seized

with his left hand the assassin’s wrist, and wrung it with such

strength that the knife fell from his stiffened fingers, and Caderousse

uttered a cry of pain. But the count, disregarding his cry, continued

to wring the bandit’s wrist, until, his arm being dislocated, he fell

first on his knees, then flat on the floor.

The count then placed his foot on his head, saying, “I know not what

restrains me from crushing thy skull, rascal.”